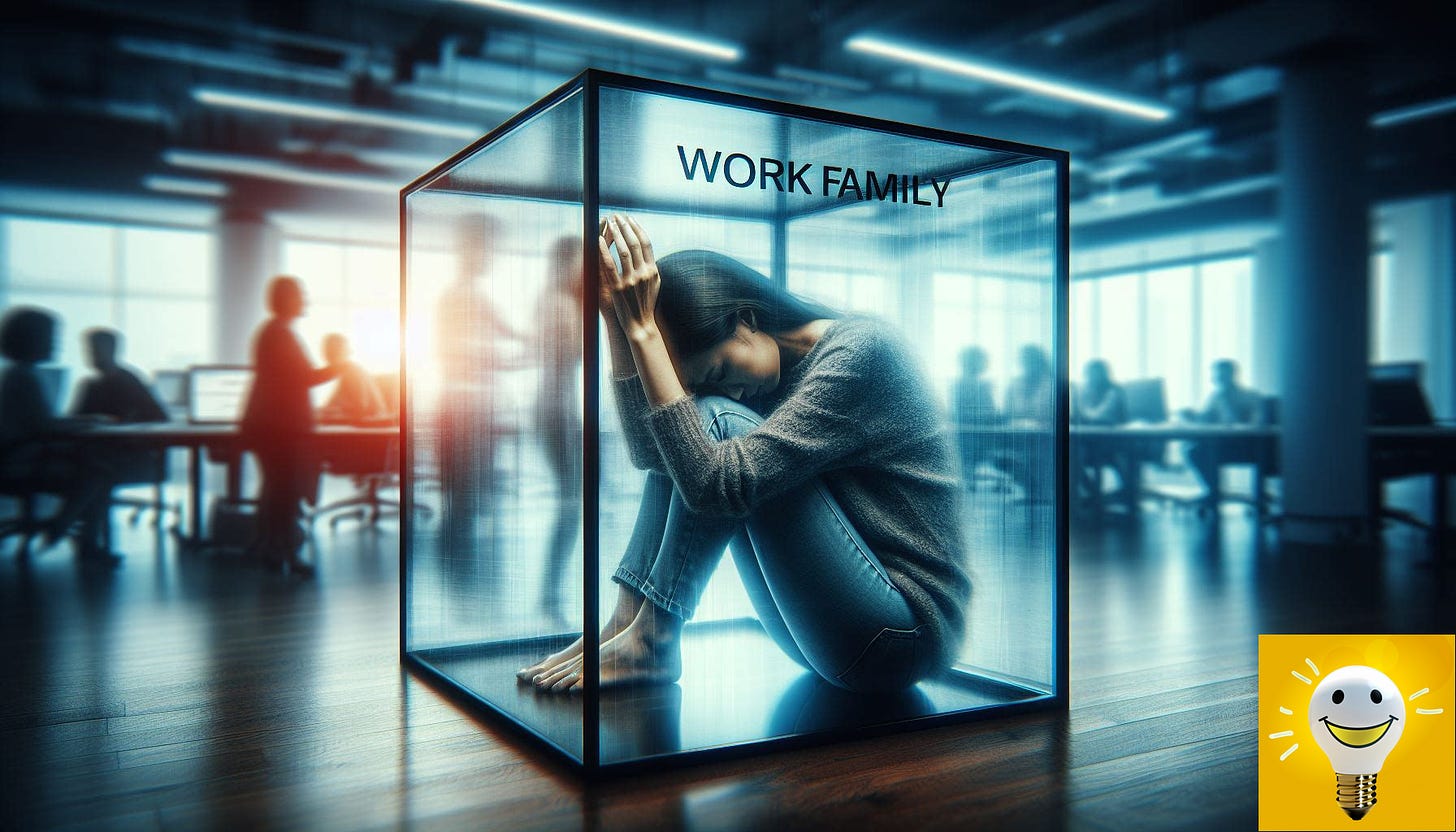

How "Work Family" Culture is Ruining Your Life!

Why Calling Your Job a 'Family' is Toxic and How to Escape the Trap.

You've probably heard it before at your job - some well-meaning manager or executive referring to the company as a "family." Every time I hear anyone using this expression, my immediate reaction is to say something like:

"Family, you can borrow money with lower interest."

"Family, will remove your pimple for fun and free of charge."

"Family had saw you naked more than one time, by accident."

My jokes aside, I understand that when people say, "We are like family," it's meant to convey a sense of warmth, belonging, and togetherness as you all pull in the same direction. It's the kind of place with laid-back break rooms, beer on tap, and bonded teams that get through everything together.

It sounds nice, doesn't it? Familial camaraderie replacing cold corporate sterility. Except...what if this seemingly innocent phrase is actually quite dangerous? What if calling our workplaces "family" breeds an unhealthy blurring of boundaries that leads to burnout, resentment, and personal crises?

Gloria Chan Packer, a mental wellness educator and former burnt-out corporate leader, makes a compelling case for this. As I investigated the issue, I realized just how insidious and widespread this "work family" mentality has become—even at companies that fancy themselves progressive and employee-friendly.

The Overworked Product Manager

Take Sarah, a fictionalized but absolutely plausible Senior Product Manager at a mid-sized tech startup. Before I continue, even though Sarah here is fictional, she was inspired by several other product managers, including myself, so if you identify with her, it is not a mere coincidence.

Sarah is extremely passionate about her work and invested in her team's success. She prides herself on always going the extra mile. "We're like a family here - we do whatever it takes to ship great products and delight our customers," Sarah's boss is fond of saying at all-hands meetings. Sarah has certainly walked the talk, routinely pulling 60-70-hour weeks, answering Slack messages and emails at all hours, and making her work the top priority above most other aspects of her life.

After all, when you think of your coworkers as family, don't you want to give them your total effort and dedication, no matter what? Saying no or establishing firm boundaries can feel like letting your "family" down.

For a few years, Sarah was able to power through her overwork, buoyed by the excitement and camaraderie of building something great with her "work family." But then the long hours, missed vacations, lack of personal time, and sedentary work lifestyle began to take a mental and physical toll.

Worsening anxiety and insomnia made her productivity and focus suffer. She began getting frequent migraines and wondered if it was due to staring at screens for too many hours each day. Weekends that were supposed to be sacred recharge time were increasingly eaten up by a need to catch up on overflowed work - or worse, spent simply lying in bed, detached and unable to motivate herself.

Sarah realized she was teetering on the edge of burnout. But after so many years of being praised for her "family" dedication and grueling work ethic, part of her felt ashamed for being unable to keep up the frenetic pace. And so she kept grinding away until she crashed utterly, ending up on medical leave.

As she began working with a therapist and reassessing her life, Sarah realized how toxic the "work-family" culture had been. By encouraging unhealthy enmeshment between her identity and her job, the warmly intended "family" platitudes had effectively stripped away her boundaries - making it feel wrong or disloyal to prioritize basic personal needs or set limits around her working hours.

The Need for Separation and Boundaries

This gets to the crux of why calling work "family" is so fraught, as Chan Packer outlines. Work and family are fundamentally different entities with different goals, expectations, and responsibilities. Deliberately blurring the boundaries between them undermines our basic human need for separation.

As Chan Packer says:

"I'm not going to be in the shower one day and notice a really weird mole on my pregnant belly and roll into my boss's office like I would my mom and be like, 'Hey, can you get in here and look at this? This looks kind of weird. I'm freaked out.'"

That example is played for laughs, but it illuminates how conflating work and family inevitably leads to violating personal boundaries that would be utterly unacceptable in a healthy relationship. Could you imagine actually doing something like that with your boss or coworkers? Of course not - because our workplaces and families occupy separate spheres of our lives for good reason.

While the specific details may vary across cultures, every human society has maintained some degree of separation between the professional/economic sphere and the private/domestic sphere. That separation is about maintaining boundaries - communicating and upholding our personal needs, identity, and autonomy distinct from other competing domains.

As Chan Packer describes, these boundaries around personal needs start forming in early childhood as basic survival instincts. "Being able to say, 'I need to eat,' 'I need to rest,' 'I need some space right now.'" And while we may sometimes strategically delay or deprioritize those needs in certain situations, a lifetime of chronic unmet needs is incredibly unhealthy.

Unfortunately, that's exactly what many modern workplaces encourage through their insidious "work family" cultures - the blurring of boundaries where we no longer feel entitled to prioritize basic personal needs over professional ones. The "family" has unconsciously become more important than our own wellbeing and autonomy.

Personal Blindspots and Poor Boundaries

Now, to be fair to the well-meaning managers and executives out there, Chan Packer is quick to point out that our struggles with boundaries and burnout aren't solely the fault of our workplaces. We each have to take some personal accountability as well.

See, many of us bring our own blindspots, bad habits, and poor boundaries into the workplace that can get activated and amplified in toxic ways. As Chan Packer shares through her own poignant story, she was already burdened with tendencies toward perfectionism and people-pleasing that originated from her childhood - tendencies that became mal-adapted into chronic overworking once she entered her corporate career.

I suspect most of us can relate to that on some level. Maybe we grew up in an environment that emphasized self-sacrifice over self-care. Or where our self-worth was inordinately tied to external achievements and the approval of others. Or where we had to adopt unhealthy coping mechanisms just to get our basic needs met.

Whatever the root causes, those kinds of dysfunctional patterns from our past get brought into our adult life and workplaces in the form of reflexive thoughts, behaviors, and even shaky senses of identity. "Work is my entire worth and identity," Chan Packer remembers thinking at one point. "I don't know what I'm going to do without it."

So when we land in workplaces that profess a "family" culture, those old wounds and poor boundaries can get re-triggered in really destructive ways. Our tendency to over-commit, avoid saying "no", or define our self-worth through eternal achievement ends up thriving in atmospheres that demand such overwork and self-sacrifice as proof of loyalty to the "family."

The end result? Feeling trapped in recurring cycles of over-extension, depletion, and burnout. But because these patterns feel so reflexive and subconsciously rooted, it becomes hard to break the cycle - even when, rationally, we know it's incredibly unhealthy.

First Steps Toward Change

So what can be done? How do we start undoing the pervasive "work family" mentality and all the dysfunction it breeds?

Well, Chan Packer's core advice is to start by doing the hard work of building self-awareness around our own personal blindspots and motivations. She suggests reflecting honestly on when and why we first developed tendencies toward overworking, people-pleasing, or blurring personal boundaries.

By tracing those habits back to the specific childhood experiences or past environments that made them rational coping mechanisms at the time, we can start to develop more compassion and choices around whether to keep operating that way in our current life circumstances.

The example Chan Packer walks through in her talk - of speaking directly to that overworking, perfectionistic part of yourself with understanding and gratitude while firmly setting a new boundary - is a powerful model for beginning this process of re-patterning our behavior in a healthier way.

Of course, that kind of deep self-examination isn't easy. Our blindspots and maladapted coping mechanisms tend to be heavily reinforced by years or even decades of habit and identity formation. Unraveling that doesn't happen overnight.

But even for those not ready to dive into that level of personal growth work right away, Chan Packer offers some smaller first steps toward detoxifying the "family" mindset at work:

First, get clearer and more intentional with your language. If you want to convey organizational values around trust and camaraderie, say that directly instead of lazily falling back on "family" terminology that can enable unhealthy blurring of boundaries. As Brené Brown says, "Clear is kind. Unclear is unkind."

Second, start modeling and overtly communicating healthy boundaries yourself - even if it feels uncomfortable at first. When asked to take on new projects or commitments, practice pausing before answering so you can check in with your current bandwidth. Or get in the habit of explicitly naming and protecting your personal needs: "If we need to move up that deadline, I'll require an extra resource or it will impact the quality."

The key is to start normalizing the straightforward expression of personal limits as something that's acceptable and even necessary in a sustainable, high-performing workplace. That's the opposite of what happens when work masquerades as "family" - suddenly, any boundary-setting can be perceived as a form of disloyalty.

Finally, look for ways to actively promote mental health personal growth opportunities within your workplace, whether that's offering better employee assistance programs, setting up resilience training, or simply destigmatizing conversations around therapy and emotional wellbeing. As Chan Packer argues, we seek out experts and education for every other important domain of our lives, like physical health or finance - so why do we so often assume we should be able to handle our mental health entirely alone?

Prioritizing Sustainability Over Intensity

At the end of the day, the problem with pushing a "family" culture at work is that it romanticizes and prioritizes an unsustainable level of intensity over sustainable performance. It says we should be willing to sacrifice basic personal needs and boundaries for the institution, treating the workplace as an inseparable part of our identity.

But human beings simply are not wired to operate that way indefinitely without consequences. We're not machines that can give 100% of ourselves to a singular pursuit or cause at all times. We're integrated wholes that require balancing multiple domains - professional, personal, social, psychological, and physical. Ignoring or suppressing any of those areas for too long leads to breakdowns.

High-performing organizations should strive for a culture of sustainable excellence. It is one where people can bring their full abilities and talents to their work, but not at the expense of nurturing the rest of their personal resources, relationships, and wellbeing, which allows them to be high-performing in the first place.

That takes leaders who prioritize maintenance and recovery periods, not just intense sprints. It takes explicitly celebrating and rewarding boundary-setting as a skill, not subtly punishing it. Ultimately, it means relating to employees as respected partners and colleagues first—not blindly elevating the workplace to a familial level of primacy that distorts healthy attachments and self-identities.

Because, at the end of the day, we all have one real family. While our workplace is unquestionably an important part of our lives, it should never be allowed to consume our entire lives. Keeping that separation through clear boundaries allows us to avoid the dysfunction of burnout cultures and find more integration across all areas of life.

So, let's retire the "work family" framing once and for all. As alluringly warm as it can sound on the surface, it far too often creates unhealthy enmeshment that slowly robs us of ourselves and our humanity. We are so much more than just our jobs, and smartly maintaining those separations allows us to invest with clarity and sustainable intensity in each of life's key domains.